I was recently told I have the spine of a man 20 years my senior. While I wish the remark had been complimenting my bravery, it was in fact a reference to my back’s lumbar region. My orthopedist said it as he showed me my MRI images.

It seems that arthritis is having its way with my vertebrae. You wouldn’t know it to look at me. I stand up straight. I walk with purpose. I appear hale and hearty.

My back feels fine.

Except for the part that doesn’t. That part really doesn’t. And it’s that part that led to my getting the MRI in the first place.

Whatever havoc arthritis might be wreaking is unconcerning at the moment. My bones may one day turn to dust, and I’ll crumble like a controlled demolition of an old casino, but right now my back has more pressing issues. Specifically, nerve-pressing issues.

I confess that I rarely think about my spinal discs. I don’t check in to see how they’re doing. I take for granted that they’ll just help me to move, allow me to bend, that kind of thing. So I was disheartened to learn that one of them buckled under pressure, herniating all over the place.

Even more disappointing, an uninvited guest has turned up in my spinal canal. It rhymes with “humor” but isn’t nearly as funny. Because it’s small and annoying, and I wish it would just go away, I’ve named it Elmo.

Elmo is literally on my nerves. My orthopedist said it could be either Elmo or the herniated disc that’s been shivving me in the back since June. He explained that this is where he must pass the baton to a neurosurgeon.

Leaving the ongoing pain out of it, there’s a story to be told about the journey I’ve been on for the last five months. The weeks and weeks spent waiting for appointments to see doctors and get diagnostic imaging. I grew a knee-length beard during the MRI preauthorization process alone.

Yes, there’s a story to be told there. But this is not that story.

Call me

I really don’t want to have back surgery. I listened to the podcast Dr. Death when it came out, and watched the subsequent limited series based on it. Together they soured me on the idea of hiring someone to do repairs on my load-bearing wall of bones, or the electrical system it houses.

My orthopedist said surgery was a possibility, but that the neurosurgeon would make that call. He referred me to a Dr. Egan.1 It was a month before he could see me.

Two days before the appointment, Michelle, a woman from Doctor Egan’s office, called.

“Is there any chance you could come in today, or maybe tomorrow, instead of Thursday?” she said.

“I can’t today, but tomorrow could work,” I said.

“Okay, great. We’ve had to juggle the schedule around because of an incident in the O.R. this morning,” she said. “How’s 1:00?”

She said it so casually, like their calendar was upended by a blizzard, or an overturned tractor-trailer on the turnpike, or some other relatively common occurrence that was not a mysterious event in an operating room.

“1:00 is great,” I said.

The next morning, Michelle called back.

“I apologize for the additional call, but could you possibly come in at noon? We’re trying to accommodate everyone and reschedule things because of what happened yesterday. Dr. Egan now has to be in surgery this afternoon.”

I felt like I’d missed a staff meeting. What happened yesterday? All I knew is that whatever it was, it occurred in the O.R. Was there an extremely localized earthquake that destroyed just that one room? Did the DEA bust in and arrest the anesthesiologist for running an illegal propofol ring? Perhaps God Himself came down, healed the patient, and took everyone out for smoothies?

Michelle sounded frazzled, so I didn’t ask any of these questions.

“Uh, let me see,” I said, checking my calendar. “Yeah, I can make noon work.”

“Great. Thank you for your flexibility,” she said.

As I was getting into my car at about 11:00, she called again.

“Is there any chance you can come in at 11:30?”

I was starting to hate Michelle, but had to admire her gumption.

“I’m leaving right now,” I said. “I’ll get there when I get there, but it isn’t going to be 11:30.”

“Okay, I just wanted to check. Someone just cancelled, so we have an opening, but 12:00 is fine. But if you arrive earlier just come right up.”

As opposed to what? Sitting in my car, waiting for another call from you?

I was glad I’d already booked a future consultation with another neurosurgeon because so far, this crew was giving me more anxiety than Elmo. I had to remind myself that this was a medical practice, not some flake selling used lawn furniture on Facebook.

Quite an operation

I got to the office at 11:45 and, given the feverish phone calls, thought they’d rush me right in to see the doctor. That was foolish. No one ever waits less than 20 minutes in a doctor’s office. It’s an AMA mandate.

Finally, a physician’s assistant took me back to an exam room.

She did my intake and was about to leave when she said, “Doctor Egan will be with you in a few minutes. We’re a little discombobulated because of what happened yesterday.”

“Yeah,” I said, the very embodiment of nonchalance. I didn’t want to appear overly interested. “I heard something happened in the O.R.?”

“Well,” she said, her voice dropping, “don’t tell anyone I told you this—we were told not to say anything.”

Michelle must have been in the bathroom when they made that announcement.

“Okay,” I said.

“There was a fire,” she said.

What the fuck now?

“A fire? How did that happen?”

“I’m not sure,” she said.

“Was anyone hurt?”

“A couple of people got burned a little, but not seriously.”

“The patient?” I asked.

“No, the patient is okay.”

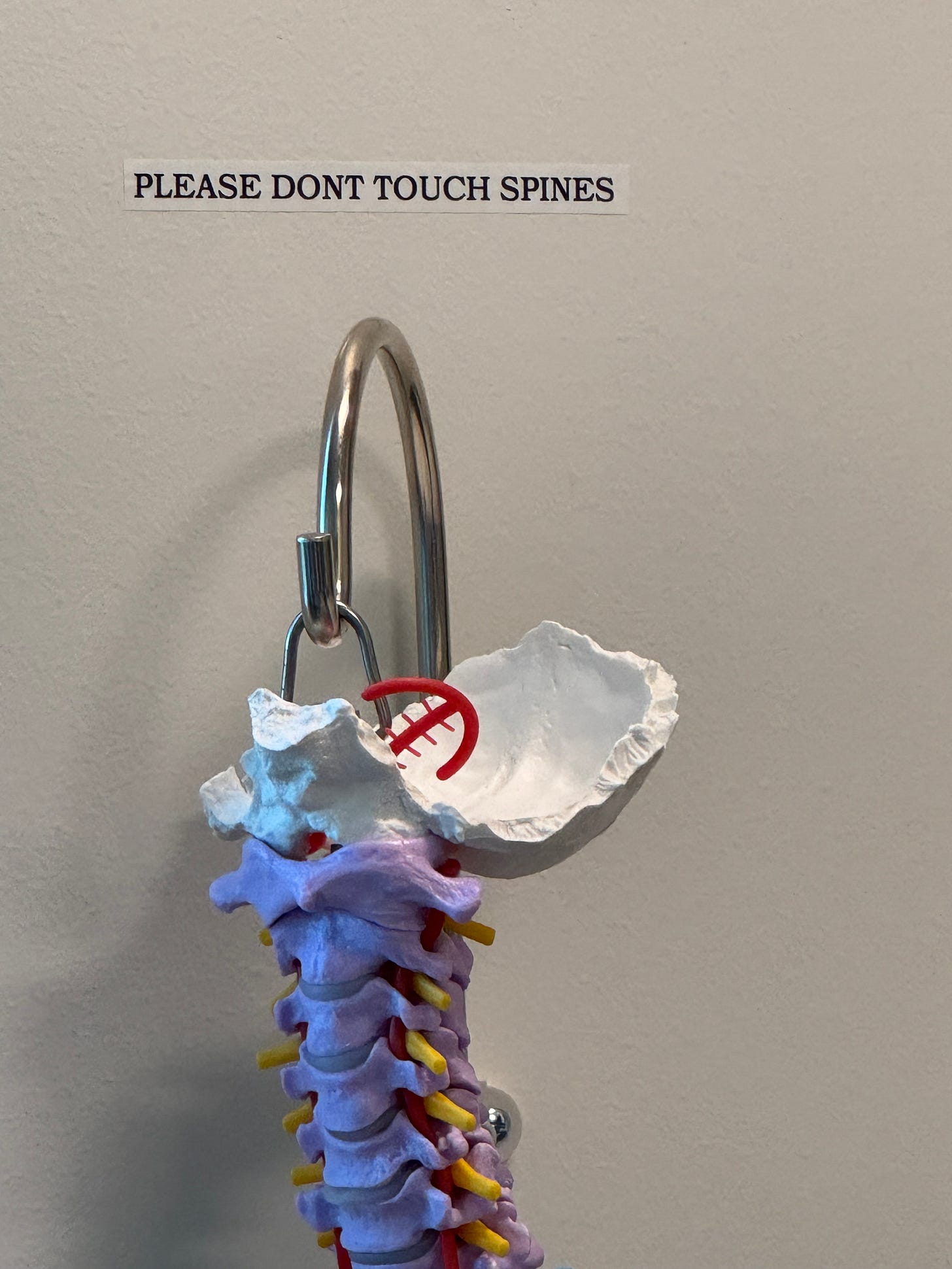

When she left me alone in the exam room, I felt a little discombobulated myself. To my left, at eye level, a multicolored, anatomical model hung on the wall with a label above it that said, “PLEASE DON’T TOUCH SPINES.” That sounded like great advice.

Dr. Egan came in, and after the customary chitchat, took me on another guided tour of my MRI images, with an extended stop at the L4-L5 region. In layman’s terms, the neighborhood is in decline.

He was about to sit down. I found it odd that he hadn’t even mentioned Elmo, so I asked about it.

“Oh,” he said, clearly not assigning much importance to the matter. He flipped to an Elmo-centric image. “This is most likely a nerve sheath tumor.”

He said the magic word—benign—and explained that he didn’t think Elmo was contributing to my symptoms. He suggested we do MRIs every two years to monitor its growth.

My relief was immense. I planned to keep the appointment for a second opinion, but it seemed as if Elmo was harmless. At least for now.

As for the crime scene at L4-L5, he took me through my options. I could schedule surgery now, but he laid out other treatments for me to consider, including steroid injections, before taking that step. I was grateful at how thorough he was, and that he took the time to answer all of my questions.

Then he said something that would finally give me insight into my biggest question of all.

“By the way, thanks for coming in early. There was an incident in the operating room yesterday so we’ve had to move other surgeries and appointments around, and it’s been a little crazy around here.”

“No problem,” I said, playing it cool so as not to tip him off that the P.A. had broken protocol. “What happened in the operating room?”

“It was a fire, actually.”

“Wow,” I said. “How did that happen?”

“It was the bed. We think it was an electrical short.”

“Whoa,” I said. I doubt that’s mentioned in the hospital’s liability waiver.

“Yeah, it was crazy. I was just about to slice into this woman’s head when I saw the smoke.”

As a courtesy, he mimed moving a scalpel in a cutting motion in case I was having trouble picturing what slicing into a person’s head might look like.

“Oh my God,” I said. “That’s really scary.”

“It was. She was unconscious, obviously, and the bed was on fire, and we had to get her out of there quick. Which we did, thankfully.”

This was beginning to sound like the kind of movie The Rock would be in.

“Was anyone hurt?”

“Not seriously. Everyone’s okay.”

With that, he stood, so I did too. He told me to keep him posted on everything: my pain level, how the meds are working, my decision about the injections, and if I want to pursue surgery.

I thanked him and thought of something important I should ask.

“Oh, one more question, if you don’t mind,” I said.

“Sure.”

“If I do decide to get the surgery, approximately what are the odds that the bed will catch on fire?”

“Hopefully zero.”

Not his real name.

I was in the same place when I was in my 40s, screwed L4-L5, and we were talking about surgery or maybe disk replacement when the surgeon I was consulting with said, “Look, if you can stand it for a couple years, I find that most men have a natural hardening of the cartilage around the time they turn 50 and for some, the pain simply goes away.” Dammit, it did! By my mid 50s, my back pain was gone. It’s my only experience with aging making pain better, but I’ll take it.

Well first, Chris, I'm glad Elmo is benign. (There's a lot of potential humor in that sentence, but I'm being sincere.) Only you could get me to laugh through a story like this, Chris, and I'm so glad you did.